Moneyball is a newsletter from Koble exploring the limitations of human decision-making and their implications for startup investing.

We’ve spent four years developing our groundbreaking algorithms, which discover early-stage startups that outperform the market and predict their probability of success.

This week

🧠 Mental Model #33 – On Madness (Part II) – Abnormal People

📖 Investor reading – Can Roelof Botha keep Sequoia Capital ahead in the AI future? – EIB calls for more innovation financing in EU – Secondaries volume reaches H1 record as venture subset continues to grow

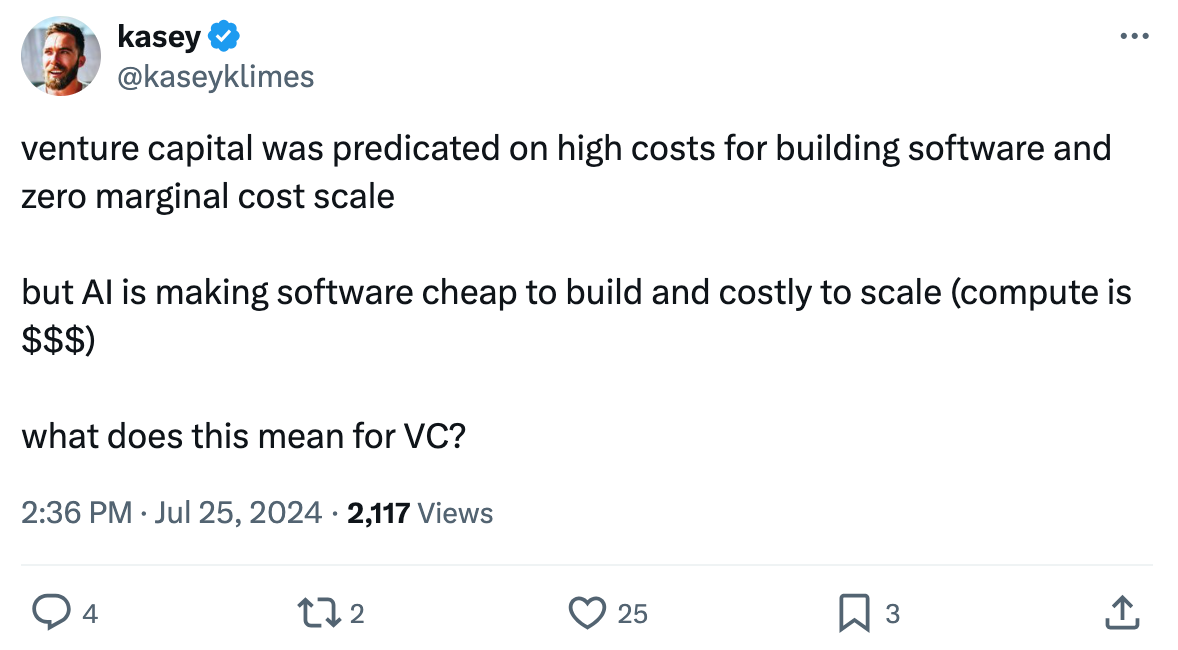

💬 Some tweets – A spike of interest that mostly dissipates – Deals from a bygone era – AI is making software cheap to build and costly to scale

Abnormal People

Startup building is presented as rational.

Founders position themselves as vehicles for penetrating insights into human nature and behaviour, capable of translating intelligence into action. And VCs like to think (and talk) of themselves as futurists, backing technologies that “make the world a better place” (especially for their LPs).

Nobody talks about madness; the invisible hand of innovation and progress. But the inconvenient truth is that irrationality and abnormality have played a key role in the history of startups. And they will continue to carve out the future of technology, culture, and human progress.

In last month’s Moneyball we looked at madness through the macro lens of tech’s biggest personalities, individuals of destiny like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk. But what about the long tail? The same logic (or lack thereof) applies – the startup world, across its entire spectrum, runs on madness.

The most transformative ideas, operational practices, and business models arise from thinking that defies conventional wisdom, and behaviors that seem irrational to the mainstream.

Launching a startup is a terrible idea (most of the time). The odds are stacked against you, VCs are stacked against you.

And even if you are top quartile, keep your feet on the ground – your chances (not your investors’) of a successful exit on cash-friendly terms are minuscule.

The story of Rovio and Angry Birds is a powerful example of how madness – in the form of dogged persistence, unconventional thinking, and frankly very weird taste in art – can lead to remarkable success.

In 2009, Rovio was a small gaming studio in Finland on the verge of bankruptcy, having produced over 50 unsuccessful games. Then it hit upon the idea of launching a simple, physics-based puzzle game featuring disgruntled birds and green pigs. This seemed a) mad, and b) unlikely to stand out in the crowded mobile gaming market.

But the concept was powerful and the game, addictive – however crazy it seemed. Co-founder Mikael Hed observed:

“When you had to shoot the bird once to test a feature, you accidentally started playing the game for 15 minutes, and there would be five guys watching you.”

When a co-founder’s mother ended up burning her Christmas turkey because she was busy playing a pre-release version of the game, the team knew they were onto something. And Angry Birds became a cultural phenomenon, spawning a franchise that includes merchandise, movies, and theme parks. At IPO in 2017, the company was valued at over $1 billion.

Madness can blind people to dysfunctional beliefs and behaviours. It can also bring light, helping to illuminate a future that nobody else can see.

In 2008, the idea of creating a social network for coders centered around a version control system seemed impossibly niche and unlikely to attract a broad audience. At the time, many developers were content with existing tools and saw no need for a new platform. On paper, it was a crazy idea.

But the founders of GitHub were convinced that making Git easier to use and creating a community for coders would revolutionise software development. Their counter-intuitive bet on open source collaboration paid off handsomely. In 2018, Microsoft acquired the company for $7.5 billion, validating the co-founders’ seemingly mad vision.

Implications for investors

Why is madness such a powerful force in startups? A few ideas for investors to consider:

Startups attract outsiders; people who have rejected (or been rejected by) large corporations that have become bureaucratic, sclerotic, and stagnant

It takes a certain type of individual – persistent bordering on obsessive; self-assured bordering on arrogant; detail-orientated bordering on pedantic; visionary bordering on delusional – to ideate, launch, and operate a business that does something totally new

Massive value creation at unicorn-scale depends on creating huge user-bases, which is easier (and cost-effective) to do if you forge entirely new markets based on iconoclastic ideas

Abnormal people are often charismatic and interesting, which makes it easier for them to attract talent (often fellow crazies)

The incentivisation model for early-stage startups attracts economically irrational people who are willing to work for “free” for order to build long term value through company ownership

Reality distortion is a sustaining force in the early years, helping founders overcome dark psychological times, financial challenges, and criticism from family, friends, investors, customers, employees and customers (basically everyone)

There are many more reasons why madness matters in startups, but these ideas encapsulate the basic truth that few 100% bonafide “normal” people build startups, and even fewer successfully exit. And they suggest some ways for investors to think about high-level portfolio construction, company selection, and founder management.

Obsessional, irrational, emotional, abnormal… All necessary ingredients for founder success, perceived as “bad” by business-school-trained VCs lacking in life experience. Perhaps that’s why exited-founders make such great investors – they understand that sometimes what’s “bad”, is good.

Observing this dynamic forces us to question what is normal. Perhaps madness in founders and startups is a kind of transcendental truth? A glitch in the Matrix that appears to “normal people” as a bug, but alludes to a higher way of thinking and living?

This paradox is neatly captured by Joseph Heller's satirical war novel Catch-22:

“There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which specified that a concern for one's safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind […] Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn't, but if he was sane he had to fly them.”

Like the pilots of Catch-22, startup founders are sane in their madness. After all, they keep flying and building, despite the risks. This is the opposite of the reverse-engineered business idea with pre-mapped milestones and intricate fundraising strategy. And it’s why early-stage founders who talk about “exit routes” and “being acquired” sound strangely cold and cynical (and are best avoided).

Ultimately, unicorn founders are anomalies that generate exponential wealth for investors, employees and the ecosystem of other entrepreneurs that cluster around their businesses. They simply shouldn’t exist. Their statistical persistence bears witness to the enduring power of madness.

The inconvenient truth is that madness is a crucial part of startup success. And investors cannot afford to ignore it.

Work with Koble

At Koble, we’ve spent four years developing our groundbreaking algorithms, which discover early-stage startups that outperform the market and predict their probability of success.

We’re working with forward-thinking angels, VCs, family offices, and hedge funds to re-engineer startup investing with AI. If that resonates, get in touch.

Investor reading

🤖 Can Roelof Botha keep Sequoia Capital ahead in the AI future? – Sequoia's culture from the get-go has been one of near-paranoid competitiveness, ruthless honesty, and a constant need for change.

🇪🇺 European Investment Bank calls for more ‘innovation’ financing in EU – A new report highlights the “critical need” of removing investment barriers in order to channel savings into key areas of the EU market.

📈 Secondaries volume reaches H1 record as venture subset continues to grow – Evercore’s latest Secondaries Market Review paints a reassuring picture for the multiple new entrants to the venture secondaries market.

Some tweets

Parting shot

“He was going to live forever, or die in the attempt.”

― Joseph Heller, Catch-22

Regards from your [abnormal] startup investing AI,

About Koble

Koble is re-engineering startup investing with AI, applying quantitative strategies that have disrupted public markets to early-stage startup investing.